A Conversation with Poet, TV Writer, and My Person, Tommy Pico

An interview with the prolific writer who has turned me into the type of person who says “my person.”

I’ve been a fan of Tommy Pico for years. His debut book-length poem, IRL, catapulted him to literary stardom, earning a New York Times profile and a Whiting Award. He followed it with Nature Poem, Junk, and Feed, racking up more accolades than a Victorian headpiece: an American Book Award, two Lambda Literary Award finalist nods, a New York Times Notable Book, and a New Yorker profile, to name a few. He’s read everywhere—from classrooms to concert halls—and co-hosted the smash-hit podcast Food 4 Thot. Originally from the Viejas Indian Reservation of the Kumeyaay Nation, the Brooklynite-turned-Angeleno has since made waves in TV writing, with credits including Reservation Dogs and Resident Alien.

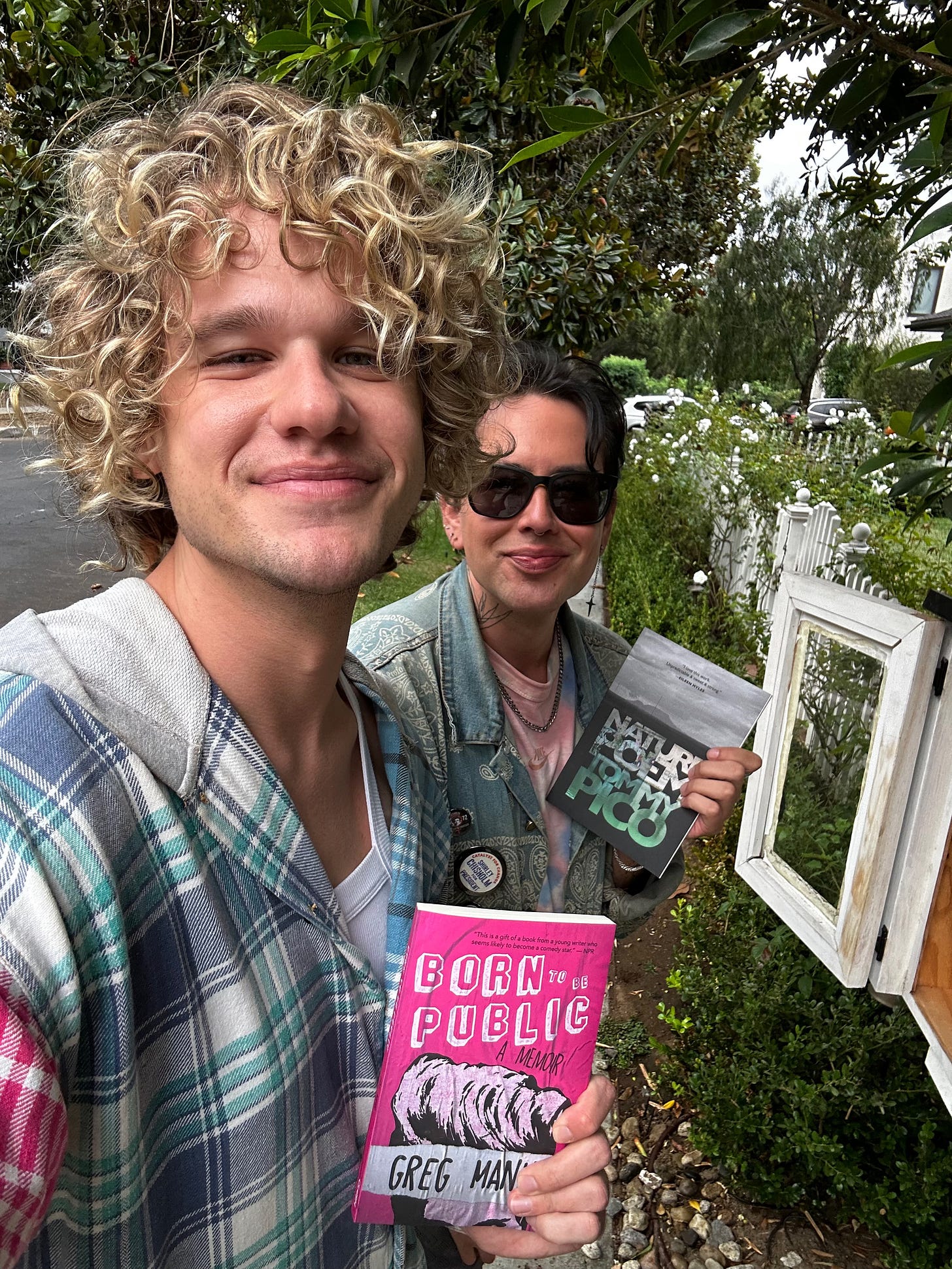

I met Tommy a little over a year ago at Morgan Parker’s Los Angeles Times Festival of Books afterparty. I spent the better part of an hour debating whether to introduce myself or stop, drop, and roll away. One of the greatest writers of my time was just a few feet from me—his glow, smile, and laughter a Siren’s lure. I knocked back my drink and went for it. By the end of the night, when he told me to put his number in my phone, I knew my life was about to change—because I already couldn’t remember what it had felt like before him. (And honestly, this flagrant display of sincerity is ruining my image as a rotted homosexual from hell!!!!!!!!!)

A few months into dating, I re-read Feed—my favorite of Tommy’s books and the final installment in what he calls the “Teebs tetralogy,” an exploration of self through love, sex, crushes, hookups, art, music, friendship, loneliness, nature—and always, his signature sense of humor. It’s also about navigating the world as a Native person under the constant specter of American violence and colonialism. The through line, though, is how it traces the evolution from Teebs to Tommy—a persona-to-person evolution. I remember reading it the first time and thinking, We’d be best friends if we ever met.

I felt like I was re-reading the book through him—not through his eyes, but through everything I now know about him. His humor, his patterns of thought, his rhythms. I could hear the conversation between Teebs and Tommy, could see where Tommy began to sprout from Teebs—not just because I recognized his voice, but because I recognized the heart that shaped it.

Greg Mania: I can’t remember if you’ve told me this before, but have you ever dated another writer?

Tommy Pico: Hm. I’ve never dated a person who was known for their writing. Let’s just say that.

Greg: What’s it like? And careful, I’m in the room; I can hear you.

Tommy: I feel like the wages of dating a writer show up later. I don’t believe writing is a talent; I believe it’s a skill, one that stems from a talent for storytelling. And it’s a hard-fought, hard-won process to finally get to a place where you can say, “I’m a writer.” It takes a long time.

When we met, I was finishing work on a TV thing, but for most of our relationship, neither of us had been actively writing what we considered our next “big thing.” I met you after your book was published; you met me after I’d published four. There wasn’t that sense of being in the trenches together. It was more like we’d already arrived.

Greg: And we both know what being a literary citizen is like.

Tommy: Which I have been, and continue to occasionally be: hosting things, doing interviews, attending events, traveling for gigs, teaching at low-residency MFA programs, visiting classes—the same kinds of things you do. It’s a particular part of the job—a big part—that very few people have real context for. Most of our friends get it, because they’ve done and still do it. Being with someone who understands that, and who still does it, is comforting. I don’t have to explain that part of the job to you—and vice versa.

The only difference is, I’m a few years ahead of you in the sense that—

Greg: You’re older?

Tommy: …Well, I’m definitely more mature. But, what I mean is, you’re learning lessons I’ve already learned. Like how to say no. How to tell people you’re overwhelmed. How to say, “I can’t keep being a literary citizen before I make time for my literary instinct.” I’m a part of this because every once in a while, I go off and write something I want people to read. But if I’m always being a literary citizen—doing all the gigs, interviews, tours—I don’t have time to fucking write. And that doesn’t just mean sitting down to actually write. It means taking time to think, to unplug, to set boundaries.

Greg: That is definitely something you’ve taught—and continue to teach—me.

Tommy: And what you’ve given me is a renewed sense of play when it comes to writing. Your enthusiasm for your projects is something I feel like I lost for a while. Not because my projects weren’t worthy, but because I was on my feet for years: writing, touring, writing while touring, editing, touring again—nonstop. And then came COVID. Then this major career pivot into TV writing, which took precedence over anything literary. But getting back into poetry, releasing new work, revisiting my original ideas—rediscovering the magic of writing—that’s something you gave me.

Greg: I love that. And I love you. For me, this past year has been a reckoning and a reconciliation, a divergence and a convergence, all of it. It’s been everything at once. What you said about saying no is something I’ve had to learn at turbo speed. I’ve had to say no to so many things in the past few months simply because I don’t have the bandwidth to keep doing what I’ve been doing for so many years.

Now, I’m learning not just how to be selfish, but the necessity of being selfish. And that’s something you’ve really instilled in me—among other things, heh, heh, heh.

Tommy: MOVING ON.

Greg: I’ve always endeavored to be a conduit of culture—to support, amplify, and pay it forward in ways that buoy the collective. But you’ve made me realize the reason I started doing all of this in the first place: to contribute to the culture.

Tommy: You don’t just want to be a commentator; you want to make the things people comment on.

Greg: That’s exactly right. And that brings me to my next question: We’ve also recently become writing partners. What are some similarities you’ve noticed between dating me and working with me?

Tommy: That you’re frustrating in exactly the same way.

Greg: Okay, fair.

Tommy: I think when it comes to writing, we both write with a persona in mind. There’s this version of ourselves that’s us, but more us. Or us, but skewed. Or saturated. But in terms of process, you’re the same. The way your ideas exist on the page is the same way they exist in the world. You’re like: What about this? That? Something in between? Or beyond? Your mind moves a million miles an hour. It’s amazing—and hilarious—to witness.

One of the things I’ve learned, which I’ve been lucky enough to pass on, is asking myself, Is this solving a problem, or creating a problem to solve? I said that to you once, and I saw you start filtering your ideas through that.

Greg: It’s about trusting your instincts, but also learning what and where the perimeters are.

Tommy: Right. When you’re pitching—and this is the thing about TV writing—you don’t want to give people barriers to thought. You want ideas to flow freely. You have to say what’s on your mind, all the time. Don’t let it fester or fade—just get it out. But that free-flow exists within guardrails. And you can put them in clearly and instantly, but it’s kind of like a strainer. What’s not meant to make it through gets caught in the net.

Greg: It’s like panning for gold. That’s something I teach my students, no matter what I’m teaching—whether it’s general nonfiction, memoir, screenwriting, whatever. I want them to treat their instinct like a muscle and practice using it until it becomes a visceral reaction they honor, instead of immediately deeming their idea as stupid, reductive, worthless—or whatever their inner saboteur, which is also an instinct (and one you have to learn to live with, but not let control you), tries to convince them it is.

When I was a screenwriting TA in grad school, we ran an exercise where students paired up. One group stayed in the room while the other waited outside. We told the students inside that they'd hear a story and then go outside to help their partners reconstruct it. The catch? Their partners could ask any questions, but they could only answer with yes, no, or maybe.

But here’s the twist: There was no story. We told the “informed” students to answer randomly. After fifteen minutes, everyone came back in—and the “uninformed” students shared wildly different stories. When we revealed that the original story page was blank, they were stunned. The point was to show how instinct and creativity kick in when you’re working from limited information. Everyone generated a story from their own gut.

Tommy: Do you implement some version of this exercise yourself now that you have more projects aligned with TV and film than with literary work? Because there’s an economy in screenwriting—you have to get in and out of a scene, constantly shift things, build arcs, all of that. When you’re originating a story and characters, do you do something similar? Or do you just sit in a room, twiddle your thumbs, and make weird noises?

Greg: Listen! Sometimes that is part of the process. When I have an idea, I honor every thought that comes through my head. It’s like there are a million people in line and only one TSA lane screening. But before I screen anything, I let that line grow with reckless abandon. I draft without budget in mind, without limits—everything is on the table. But, like you mentioned, there are guardrails that eventually come into place. That’s when my ideas start going through the checkpoint. That’s when I start shaping and molding.

Tommy: And there are times during the writing and editing process when you lean on those guardrails a little bit harder.

Greg: Exactly. Something I’ve learned from my former writing partner—the incredible Dean Dempsey, whom I’ve learned so much from after writing a pilot together and then writing and shooting a film—is that for every creative problem, there is a creative solution.

Tommy: Mhm!

Greg: Let’s talk more about persona, which is something we’ve spent many a night discussing, because we both spring-boarded into our careers as personas—you as Teebs, me as Mania—and we’ve since tried to reconcile Tommy and Greg with those monikers. How does Teebs fit into your life now?

Tommy: Teebs is the part of me that acts without overthinking—pure instinct. Not that long ago, I got some sides for a character in a TV show to shoot a pilot. I was trying out different voices and trying to embody the character, and that’s when Teebs came out. He hits the ground running. He’s not great for writing poetry, which requires more reflection, but he’s essential for making bold choices. Teebs in action is decisive, direct. Tommy is thoughtful to a detrimental degree; Teebs just does. Like that time at Hi Tops, when a guy was leaning on you and I said, ‘Do you want me to yank his ass?’ That was Teebs ready to go—but also a little Tommy, checking in before possibly getting arrested. Teebs can get too hot, Tommy too cold. Together they’re just tepid as hell.

What about Mania and Greg?

Greg: For a long time, I felt split—either I was Mania, bold and defiant, or Greg, soft and sensitive. As I started building a career—internships, bylines—that split started to mess with me. I’d wonder, Is any part of me real? Am I reacting as Mania, or as Greg? But writing grounded me. On the page, there’s no persona—it’s all of me. Past and present selves, contradictions and all. Eventually, duality became totality. I’m not either/or. I’m both.

The best example of that lives in this apartment. I signed your hardcover copy of my book as Greg Mania—cheeky and fun. But months ago, when you weren’t home, I signed your paperback as Gregory, with something deeply personal. You might find it next week, or in twenty years while we’re packing up to move. That’s me, too.

Tommy: Oh, I gave it away.

Greg: To Goodwill?

Tommy: I actually burned it for warmth during a blackout one time.

Greg: And then you gave it one star on Goodreads.

Tommy: See that just now was Teebs and Mania.

Greg: We are a detriment to the entire universe. But before we cause it to implode in on itself, there’s a question I’ve been wanting to ask you. I don’t remember who was interviewing whom, but recently I was watching two people in conversation, and one of them asked—which is what I want to now ask you: What is one thing you’ve learned from me that you couldn’t learn from anyone else?

Tommy: I’ve never felt compelled by a romantic partner to change a single thing about myself. There were superficial ways, back when I didn’t have a modicum of self-confidence, where I changed everything. I would literally become whatever somebody else wanted me to be so they would love me. There’s a line in IRL that’s like, “What I learned is you can make someone cum three times in a night and they’ll still cheat on you.”

Greg: That is so real. I’m so goddamn glad I never have to date again.

Tommy: SO GLAD. But back to what I was saying—which is, I’ve never been compelled to make substantive change in the right direction for a romantic partner before. And a question I’ve been asked—by friends, by my therapist—is: Are you afraid of intimacy? What I will say is, there’s a feral element to me having been basically single for the first forty years of my life. I say I’ve dated, I’ve been with people, but my longest “relationship” was six months. Compared to us, and our relationship, that was nothing.

I guess what I’m saying is, I’ve never met anybody who made me feel like everyone else is one color, and you’re a different color. You’re a different color than everyone else.

Greg: [Unintelligible blubbering.]

Tommy: From the second I saw you—and then met you—I felt very much in the presence of somebody I was impressed by. Someone I felt deeply for and deeply toward. And so fucking hot. And also, so incredibly kind.

For people like us to actually be kind—I don’t think any oppressed person defaults to kindness. In fact, I don’t think any human does. You have to find your way there. You have to do a lot of work to be kind. Especially in the world we live in.

Greg: Exactly—and why would you?

Tommy: Right. Especially for people living in the U.S. under late-stage capitalism—our culture doesn’t incentivize human kindness. The incentive is capital. If something leads to money, it’s seen as good. But that’s not the same as being good.

And you—right away, you were so many things that made me feel… not impressed, because that word implies a hierarchy, like I’m above you and you did something to earn my approval. It wasn’t that. It was respect. I had such immense respect for you from the beginning. I don’t think I’ve ever felt that with a romantic partner before. I mean, all humans deserve respect, so maybe that’s not the right word either. Ugh, this is what happens when you date a writer—you’re always trying to find the right word. And maybe it exists, but I can’t think of it right now. Or maybe it doesn’t. Actually that’s how I’ve felt about you ever since: I can’t put it into words.

Greg: It’s funny hearing you say that—being at a loss for words—because that’s so rare for you. Even early on in our relationship, I was always trying to say the right thing at the right moment, but I just couldn’t. I was feeling too much. For a long time, I thought, Oh my god, I’m not saying the right thing.

But eventually I realized I don’t have to. My actions carry that wordless feeling you just described. So I stopped stressing about being poetic—because honestly, that’s your job. Even when it’s late, we’ve had a few drinks, or I’m completely fried, you always turn emotion into language that, like you said earlier, I just experience. It’s magic.

For a while, I used to fret about how to express the endless wonder I felt for you. You made me feel like that film and TV trope—two characters under a spotlight while everything else fades to black. And there I was, scrambling to capture how I felt in a way that sounded prolific but came out sounding like Dick and Jane.

Tommy: I think you think that’s what you were doing, but it wasn’t. Because sometimes I think there’s a part of you that’s more against yourself than for yourself. Because all I do is marvel at you. Even when I’m frustrated! No human being—honestly, other than my brother—can make me laugh the way you do.

Greg: I think this might be our formal introduction to the world as a duo—not just as a writing pair, but also as two voices who are just as distinct together as they are alone. All of our close friends who get our voice notes have told us there should be a Grammy category for Best Voice Notes so we could win it. One of our friends said she couldn’t believe she was getting that kind of entertainment for free. Is there anything you want to say about that or whatever? Sorry, I’m tired.

Tommy: Wait, what was the question?

Greg: I don’t know even know anymore.

Tommy: Is there anything I want to say about us as a duo? No. In fact, I would like to say less. And I would love it if this entire interview was redacted. My name is Tommy Pico, and I approve this message.

Greg: Honestly, thank god, because this is getting really long. Last question: Are you finally going to subscribe to this fucking Substack?

Tommy: [Endless laughter.]

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

If you like this, consider becoming a paid subscriber today and supporting the work and team it takes to make this publication possible. Thanks for your support!

Credits

Art by: James Jeffers

You can follow my other unhinged missives by following me on Instagram, Threads, or Bluesky. Peruse my website for more work and to get in touch!

This part though "(And honestly, this flagrant display of sincerity is ruining my image as a rotted homosexual from hell!!!!!!!!!)" LOL

Like I just! Yall are my faves. Loved this whole thing.