Spilling the Tea on My OCD

I’ve been pretty open about my bevy of disorders, except obsessive-compulsive disorder—until now.

I don’t remember exactly when I started doing it. I know that it was in the fifth grade. My teacher was Mrs. Sosinski. And I remember what my interests were at the time: Milky gel pens (GAY) and birds (SAD). I had trained the tufted titmice in my backyard to eat sunflower seeds from my hand (WILL NOT HAVE SEX IN HIGH SCHOOL). I had one friend, Ulyana, a Russian girl who frequently invited me over to play with her ferrets. But other than that, I can’t really remember when I started repeatedly clenching and unclenching my fists in rapid bursts. I would do it in class, under my desk, so no one could see. I’d do it at lunch, in line after recess, in gym class. All I knew was that I had to do it, because something told me that if I didn’t, time wouldn’t pass.

It’s not a coincidence that, at the time, I had an irrational fear of tornadoes. Some context: I grew up in central New Jersey, where tornadoes were extremely rare. My mother thinks I developed this irrational fear as a trauma response to an extremely age-inappropriate haunted house that my school set up for Halloween a year prior, which is totally possible. I got so scared I was inconsolable; I couldn’t sleep alone for a few YEARS. But it’s also totally possible that the incident just engaged some dormant brain chemistry that would have become active sooner or later. In either case, I spent all of fifth grade with one eye out the window, scanning the sky for ominous-looking clouds, and the other on the clock, desperate for the clock to read half past three so I could rush home to safety.

The next thing I knew, I was doing these little hand bursts all the time, using them as a way to measure time in intervals. As an adult, I realize now that that was my way of asserting control over the uncontrollable: the weather, the time, my fears. I didn’t have specific intervals for when I’d do my hand bursts; they were arbitrary. I only did them when I felt fear creeping up on me. The logic (or attempted logic, I should say) was: each hand burst meant that the previous one was in the past, and each one to come meant half past three would eventually come around, and then I would finally be able to go home. I was convinced that if I didn’t do it, something terrible would happen.

Even though I didn’t have the language for this behavior back then, a part of me knew it wasn’t neurotypical. I didn’t see any other kid doing “hand bursts.” No one else looked visibly uncomfortable when the sky turned dark. No one else grabbed their backpack and ran straight out of the room when, one day, the sky turned completely black, just a half an hour before school was dismissed. I hid my compulsive behavior, because the same part of me that felt my behavior wasn’t rational or ordinary—my inner impartial spectator—also knew that time would pass regardless and that weather would happen anyway. But what I was doing with my hands was at the mercy of something internal, something I knew—on some level—did not influence reality, yet trying to resist it felt futile: I had no choice. At least it felt like I didn’t.

***

It’s one in morning, and I’ve been rearranging the same fucking throw pillow for over an hour now in my Brooklyn apartment, which I share with two roommates. I like to be in bed by eleven, at the latest, reading or watching old episodes of America’s Next Top Model on my iPad. But I’m in my living room, fluffing and re-fluffing, positioning and repositioning the same pillow until I think—or rather, my brain allows me to think—that the pillow looks centered on the armchair, that the chop is exactly in the middle, and that one tip of the pillow is not higher than the other. The shower I took earlier was a waste of time, because I am now dripping with sweat from a combination of frustration, both with myself and my roommate who thoughtlessly put her jacket on the chair, which fucked up the symmetry I had going, and now I’m losing sleep as a result of her heinous offense. Who uses a HOUSE as a HOME? ELECTRIC CHAIR!!!! I’m frustrated at myself for being frustrated with my roommate for doing LITERALLY NOTHING WRONG. I’m sweating even more because I’m worried one of my roommates will come out of their rooms and be like, “Why are you fluffing that pillow at one in the morning?” while staring in concern because I’m sweatier than Kristen Wiig in that diarrhea scene in Bridesmaids.

Even more exhausting is the thought that I will have to repeat this process in the morning, because everyone sits on the chair to put their shoes on before leaving the house for work. I find myself increasingly jealous of my roommates, who seemingly function at a normal capacity. They can get dressed and subsequently be out the door within minutes. I resent the fact that I can’t just grab my keys and go without a fixation like this throw pillow delaying my departure.

In the morning, I abuse the snooze button. I know my compulsive rituals await on the other side of my bedroom door, something new added to the mix seemingly every week. I’ve always been someone who likes to set their intention for the day by making the bed and putting away the dishes before starting my work. I’ve always been a clean and tidy person—curating and taking care of my space is therapeutic to me, even. Something about it just makes me feel more productive, allows the creativity to course through my veins with wild abandon. When I’m surrounded by my carefully arranged items—my books, my art, my plants, even the intensely hued colors I like to douse my space with—I feel positioned to approach my work with an open mind, ready to embrace the only mess I not just tolerate, but love: the glorious messiness that is the work of writing.

But, at some point, my preference for keeping my surroundings tidy became a compulsion. At first it was gradual, small things that clawed at my brain like a dog ready to be let in from outside, and then, all of a sudden, it felt like these compulsions had permeated every aspect of my life. Small tasks became insurmountable. I struggled to reply to even one email because I would agonize over a comma or a semicolon—deleting them, putting them back in, or just deleting the sentence altogether. I had to reread my emails a seemingly infinitesimal number of times before I could hit send, even if it was a one-sentence response.

My life did not feel like my own anymore; I felt like I was in the backseat of a vehicle operated by a stranger that I would come to realize was not a stranger at all.

***

You know how people line up around the corner of the Apple Store the day a new iPhone drops, or when a streetwear brand like Supreme debuts a new collection and all the trendy young people line down city blocks as far as the eye can see? That was me at Staples every September as a kid, hungry for new and glossy school supplies. Oh, you dreaded going back to school, wanted to keep going to camp or the beach, or to stay up late every night staining your mouth with ice pops? KEEP IT. I would happily turn over ice cream for dinner for a kiwi-print pencil case.

Oh, the euphoria. THE OPTIONS. Was I in the mood to do a single-subject notebook for each class, or just one five-subject for everything? What colors were available? Don’t be fooled: I still had specifications. The margin of my notebooks had to be MAROON. A red margin was too abrasive for my sensitive nature. The lines had to be TEAL—we love contrast! And the spacing between the lines had to be wide; my handwriting required SPACE to FLOURISH. Besides Milky gel pens (to reiterate: GAY), I was not a proponent of pens; I liked pencils, specifically the Paper Mate mechanical pencils that looked like pencils masquerading as pens. If I was feeling saucy, I grabbed a pack of colorful mechanical pencils, with different eraser colors and what have you. My folders had to be glossy, not matte, because I liked my Book Sox (DO YOU REMEMBER THOSE?) muted. IT’S ABOUT THE NARRATIVE CONSISTENCY, LEAVE ME ALONE.

In eighth grade, I kept it minimal. One black five-subject notebook— très chic!—with all my line and margin specifications, of course, and a glossy folder for each corresponding subject. I liked my teachers, my classes, BUT HATED EVERYTHING ELSE. I had one friend, Mallory, a girl who the kids in my history class thought would be fun to pressure me into asking out in front of everyone, because it’s funny to publicly humiliate the kid everyone called a homo. We were generally friendly with one another before, and she had never made fun of me, so I liked her. She ended up saying yes when I crumbled under pressure and asked her out in front of everyone, either because she didn’t want me to feel any more embarrassment, or because she genuinely liked me and didn’t care that everyone already thought we were “going out.” We didn’t do anything besides hold hands and occasionally peck each other on the cheek. It ended up working out for me because I got to carry her purse, which I thought was super cute, between classes and when school let out. I was STOKED every time the bell rang. JOKES ON U, HOES. But then she ended up moving to Virginia, and I went back to having no cute purse and no friends, the latter of which was fine. EVERYONE WAS TERRIBLE. Our entire eighth grade class was split into two, so the friends I would eventually make in high school—many of whom are still friends I have today—were all in the other group, so we hardly crossed paths. Instead, I got stuck with every bully, which made things insufferable enough. On top of all the bullying, I was also contending with a new irrational fear.

While my irrational fear of inclement weather—specifically, tornadoes—and the hand bursts that came with it started to fade into recent memory, I developed a debilitating fear of my parents getting into a freak accident and dying every time they left the house. So instead of staring out the window all day, worrying about seeing a funnel cloud developing in the distance, I was thinking about whether or not my parents had made it to work. If my mom had to go to the grocery store, I was a wreck. My parents couldn’t leave the house without me being reduced to tears; their lives—both personal and professional—were cast aside, their worries about me running parallel to my worries about them every time they went out, even if it was to the pharmacy around the corner. In an effort to quell some of my anxiety, my dad got me a cell phone, with the proviso that I wouldn’t abuse this privilege, which of course I did. I was to use it only for calling my parents or brother. I was thirteen; those limited minutes didn’t stand a chance. While being able to reach my parents anytime gave me some peace of mind, I wasn’t completely free from the grip of my irrational fear.

I sought distraction, something to serve as an outlet for all the anxious energy the circuitous thoughts in my brain generated. I started fixating on my notebook and its placement on my desk. I didn’t even notice what I was doing at first; it just became a compulsive behavior by default. When I was done taking notes—which I would do ever so carefully; I couldn’t have my handwriting starting out evenly and then going rogue a few pages later!—I would go through and make sure none of the pages had been folded over. Then, I would place them on the upper right-hand corner of my desk and repeatedly even out the sides and top so no lingering pages would stick out and then make sure each section lined up evenly by verifying the maroon margin that was visible from the outside made a straight line perpendicular to my desk. To double-check that it was even, I would look through the holes the spiral went through and make sure I could see straight through to the bottom. Make sense? IT SHOULDN’T. (Unless you’re like me, in which case, hello, babe, I see you.)

I continued performing this little ritual over and over throughout the day until one time, in eighth period English, a kid sitting next to me caught me. As usual, I never made a flagrant display out of my behavior, I always kept it on the down-low out of an intrinsic discernment that it would be seen as strange, fuel for the bullies I was trying to steer clear of. That day, the boy next to me, unbeknownst to me, watched me carry out my ritual, and once I was satisfied, he leaned over and poked my notebook with his pencil, causing it to shift. I rolled my eyes and tried to ignore him. When I thought he wasn’t paying attention anymore, I started my regime over, until my notebook was restored to its original position.

Reader, the little shit noticed.

I felt the panic inside me bubble like a cauldron. Before he could say anything and expose my secret, our teacher, Mrs. O’Keefe, reprimanded him for not paying attention. Thankfully, he listened (she was scary as fuck!) and didn’t bother me for the rest of the class. Once the final bell rang, I was still shaken up about what had happened. I felt shame starting to creep up on me, strong enough to modify my current compulsive behaviors into different ones that would guarantee inconspicuousness.

I never revisited this memory—didn’t even know it existed in some recess in my mind—until fifteen years later, when the same type of shame reawakened in me.

***

Before COVID-19, when I would leave the apartment to go to my day job, meet up with friends, visit the doctor, attend events, or commit to anything else that required punctuality, I would, more often than not, run late. Not because I lost track of time. I knew exactly what time I had to be out the door. I just couldn’t cross the threshold until I finished folding and refolding the same shirt, like, forty-seven times, or polished that sentence until it gleamed the way I know it could—knowing very well I would be running late, even if it was for something like a job interview.

Sometimes I’d be just about ready to leave, until I noticed that something looked off (to me, of course). I’d be sweating in my coat, arranging and rearranging that same fucking throw pillow on the armchair while I watched the clock on the microwave slowly creep past the last salvageable minute I would need to leave lest I ran late. I fantasized about throwing the pillow away, but I knew that my compulsion would transfer to something else. I learned that lesson when my roommate’s dog fucked up the floral pashmina we had draped over the chair; I had started to fixate more and more on the fringe that hung off of the seat, running my fingers through it until every thread lined up without interlacing, and making sure it looked even, like I was trimming my own bangs. I was secretly glad her dog fucked it up and we had to get rid of it—no more fringe to fret over! And when I got a pillow for the chair, I thought I was home-free. I thought I was just going through something, and now it’s gone. But then, slowly but surely, I started to fixate on the pillow. I couldn’t leave it alone; I kept leaving the room only to return and confirm that the pillow and its position still sated the part of me that kept coming in to check. It dawned on me that if it wasn’t the pillow, it would be the napkin holder, the coffee table, the arrangement of my books, or any other arbitrary object or objects my brain would fixate on. It felt like an itch I didn’t have enough arm to scratch. Only until everything “clicks” in my brain could I finally run out the door.

I started to feel like a bad friend, a bad son, an unreliable colleague, so when we went into lockdown, a part of me was relieved. I could perform my rituals as much as I wanted because I was home twenty-four-seven. I could “monitor” the living room if one of my roommates used it, always ready to swoop in and tidy up as soon as they were finished with it. My schedule revolved around my compulsions, so work started whenever I felt like I was done putting everything back in order. I had started to give myself ample time before Zoom meetings and calls in case compulsion called first.

To no one’s surprise: the compulsions got worse.

The problem for me was: I had to work harder at hiding my compulsions. Quarantine meant all of us were home—all the time—so the chances of getting caught doing one of my rituals were higher. The shame that I had been actively burying deeper and deeper like a duck sauce packet in my utility drawer started to creep up on me. I could get caught any minute, and then I’d have to come up with some fakakta excuse —“Oh, that’s not me repeatedly banging this pillow against my knee, trying to get all the creases out; I think the neighbor maybe fell in the shower????”— and hope it flies. And while my partner at the time, who usually spent the weekend at my place, had some knowledge of my obsessions and compulsions, I would still wait for them to fall asleep before crawling out of bed to go tidy and re-tidy the living room well after we had finished watching a movie, so I wouldn’t be asked where I’ve been for so long.

It became exhausting. It made me depressed. I was sinking in shame, not even telling my therapist about how much time and energy I was devoting to my compulsions. For so long they had crept into my routine, one compulsion after another, and it wasn’t until we were all relegated to our respective homes for over a year that I was confronted with the reality of how much I was missing out on when we were already missing out on so much. Total chunks of my day were gone, and whatever energy I did have went into my work and ensuring I was able to deliver quality material. Logically, I know the furniture looks just fine after what is deemed an appropriate amount of time tidying up. But my brain did not compute “fine,” instead it overpowered me into thinking that anything less than perfect would yield disaster and chaos.

***

In therapy—which, like almost everything else, became remote as a result of the pandemic—I was already working through multiple challenges: my depression and anxiety, my worsening chronic pain, my family hang-ups. The last thing I wanted to do was add another Thing to the overflowing well of emotional turmoil. I wanted to sweep it under the rug, mostly because I was ashamed. I unequivocally knew it was obsessive-compulsive disorder, but naming it would officially make it something I had to confront and contend with. At the time, my shame thwarted any attempt at approaching it head-on. For as long as I kept my head down, I couldn’t see how closely inextricably linked my OCD was to my other mental illnesses.

I always thought my OCD was mild. I had coping techniques to deal with obsessive thoughts when they arose. But those were thoughts; I was already well-versed in the I-am-not-my-thoughts verbiage that one comes across in therapy. I knew how to live with them. It was the newfound physicality of my OCD that was throwing me through a fucking loop. It wasn’t until I finally brought it up with my therapist that I realized it wasn’t as newfound as I thought.

When I finally mustered the courage to bring it up in session one day, my therapist asked me if I’d ever heard of something called Y-BOCS. I told her I was not familiar with that Norwegian wireless network operator. After trying to suppress an eye roll, she told me it was an acronym that stands for Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Like a good therapist, she acknowledged and commended me for taking such a huge first step in telling her, and promised that we would proceed at a pace I felt comfortable with. She asked me if I was comfortable with starting by filling out the Y-BOCS score sheet, which is a ten-item scale designed to rate symptom severity and has become the most widely used rating scale for OCD.

A doable first step, I downloaded the Y-BOCS PDF and went through each item, scoring myself on a scale of zero to four. Still in denial that my compulsions were a “phase”—“They’ll go away once I move out of this apartment!”—I thought my score would fall somewhere between sixteen and twenty-three, which is deemed as moderate.

After adding up my answers, I ended up with a score of twenty-five. According to the assessment, I had severe OCD.

I added up my score two more times—still twenty-five. Still severe. After sharing my score with my therapist, she encouraged me to talk to my psychiatrist to receive a formal diagnosis, which I got a few days later after my routine follow-up visit with her. We discussed medication options, but I opted to continue psychotherapy as the first approach, and meds later, if necessary. As someone who had finally found the right combination of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication at the time, I was reticent about adding a new prescription that could possibly send one of my other two-hundred disorders into a disarray, and then I’d have to live out the rest of my life in Child’s Pose in the middle of the forest.

To my surprise, I found comfort in being able to look at my obsessions and compulsions empirically. I stopped thinking of my OCD as this looming amorphous figure, unsure of what its next move would be or what havoc it would subsequently wreck, and started looking at it for what it was—something quantifiable. Something that is, in some way, finite. Solidifying a diagnosis also brought me solace; there’s power in naming something. By pulling back the curtain, the uncertainty and unknowing retreat, allowing for clarity and a plan for treatment. It made me a little less scared of myself to know that it’s not actually me—the arranging and rearranging, the checking and rechecking, the obsessive thoughts and fears—it’s a chemical imbalance in my brain—a misfiring of signals—and it has a name.

My therapist sent me some more documents to look over, to better acquaint both of us with all the nuances of my obsessions and compulsions. There were more scales, which zeroed in on things like medical OCD (“When I notice my heart skipping a beat, I worry that there is something seriously wrong with me”), which I scored moderately low on. A lot of these overlap with my anxiety symptoms, and I’ve utilized the coping mechanisms I’ve learned over the years to deal with them. But it was the other few sheets that made me pause, because they weren’t just things I was struggling with now, they were things that have been present in my life for as long as I can remember: worrying that if I don’t control—or try to control—my unwanted thoughts, something terrible could happen (hand bursts!); believing that certain thoughts increase the chance that something terrible will happen (dead parents!); and a feeling that things need to be “evened out” or symmetrical or else I’ll always feel uncomfortable (five minutes ago!). It was reaffirming to see my experiences reflected back at me in evidence-based assessments that are frequently used to determine the severity of symptoms. It meant that other people struggled with these things, too. It normalized it for me.

Among the literature I was asked to review in tandem with my work in therapy was a book called Brain Lock by Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz, which was re-released a few years ago as a twentieth anniversary edition. It presents a helpful four-step self-help treatment plan with the objective of changing your behavior and, ergo, changing your brain chemistry. It’s one of those self-help books that you cherry-pick from, because while there are many helpful tips and methods, there are also a lot of references to God and the Bible, which I never finished reading because I found the plot trite. (Thankfully, it’s not a pray-the-gay away situation, just a number of God-helps-those-who-help-themselves passages.) Another thing that I shied away from was the constant use of war as metaphor, constantly referencing OCD as something to be defeated. Here’s the thing: I don’t want to be in battle; I don’t want to fight something that is ultimately a part of who I am—I don’t want to fight myself. I’ve spent many years as a young adult hating and harming myself, wanting to vanquish whatever the source of self-hatred was in me and using any means to do it: drugs, alcohol, sex. I didn’t want to do that anymore. I rebuked this mode of thinking and instead worked to reframe my relationship to OCD.

Through therapy, I was able to hold space for complexity. And it’s within that space that I was able to access memories of the times my brain’s proclivity to fixate actually enhanced the world around me.

***

My ninth-grade algebra teacher, Mrs. Pineles, used chunky chalk to write on the board, the same kind you’d use to draw on a sidewalk. I loved her handwriting, and yellow is my favorite color, so when she used the yellow chalk, I would pay attention closer than most. I loved the grandiose way she looped her Y’s, the drama of her fives, the equations on the board rendered in a sort of hurried elegance I found bewitching. My brain’s fixation on the contrast between the black board and the thick yellow lines of the chalk made solving for X in equations like y=mx+b come alive for me. I didn’t feel like I was solving problems; I felt like I was finding answers beyond the questions posed by the equations.

I paid closer attention to the lessons and, as a result, ended up excelling in class—Mrs. Pineles even told me she’d recommended me for honors math courses. Looking back with the self-awareness I have now, I can see now that I had understood a language underneath the problems and equations, something my brain was able to synchronize with and could use to amplify a one-dimensional experience into something more. I wouldn’t attribute that to OCD, exactly, but it is the same brain that lives with OCD, and it is also the brain that allows me to look for beauty in the mundane.

After accessing this memory, I was flooded with others similar to it. It was like recalling a dream that I had forgotten I’d ever even had. I scrolled through my mental feed of things for which my love was deeper than surface level: the patterns I would spend afternoons creating with sand art; the endless hours I spent creating prismatic explosions of color on countless pieces of paper with my watercolors; the way I heard music—the songs I couldn’t stop replaying because my ears tasted a new flavor with each repeat; the faces I would see in flowers, like a daffodil and its expressive trumpet, with different shapes, sizes, and colors to boot; even the way I wrote my T’s in cursive; and so many more things, many of which I still love today.

Looking back, I realize I’ve been seeing shapes in clouds everywhere I’ve looked.

***

My OCD is still something I have to actively work on every single day. Some days are easier than others, but I’ve come a long way since letting a pillow insert I bought on Amazon and a banana leaf-print cover I bought on Etsy for thirty-three dollars dictate the flow of my entire day. I can tolerate mess, and clock when my desire to tidy overstays its welcome. I’ll challenge my compulsions by devoting days to not making my bed or not tidying up the living room after using it, and remind myself that it has no actual bearing on whatever it is that I think it has a bearing on beyond just looking nice and orderly.

Of course, I still get frustrated. Of course, I still find myself drawn to excess, but when I do, I remind myself that progress is not linear. There is nothing to achieve; there is no end result. The work lies in recognizing that it is something you live with, something to make space for in life without allowing it to dominate it.

Most importantly of all: I’ve stopped wishing I wasn’t like this. I no longer think of myself as cursed. By practicing mindful awareness—to an extent; I still don’t know what my rising sign is nor will I ever spend $2,000 to go spend a weekend in the woods to learn fourteen different ways to breathe (but if that’s your thing, by all means, have at it!)—I’m able to sit with my thoughts and observe them as if I’m people-watching at an outdoor café. In doing so, I can curtail any possible compulsive behaviors, because, like the people I watch when I’m outside drinking my iced motor oil with exactly one drop of oat milk, the thoughts and compulsions pass. Some days they don’t—and that’s fine! By just acknowledging these thoughts, I’m able to pay closer attention to the world around me, and sometimes what I see makes getting out of bed worth it.

I’m not saying that I love my disorder. That would be a stretch. But this is where embracing complexity comes into play; it’s not a black-and-white situation. My OCD isn’t me; but it is of me. And I don’t want to fight it, no matter how reputable the self-help book that suggests going to battle with your OCD is. First of all, I’m lazy; I’ll switch off my WiFi and just use my limited data to endlessly scroll TikTok instead of walking into the other room to reset my router. Also, the same brain circuitry that allows me to find joy in the ordinary—joy found in a place where once was pain—is not my enemy. It is an invitation to possibility.

When they say to stop and smell the roses, I don’t know where to start. I have so many different roses to choose from.

If you like this, consider becoming a paid subscriber today and supporting the work and team it takes to make this newsletter possible. Thanks again for your support!

Yours,

Greg

Credits

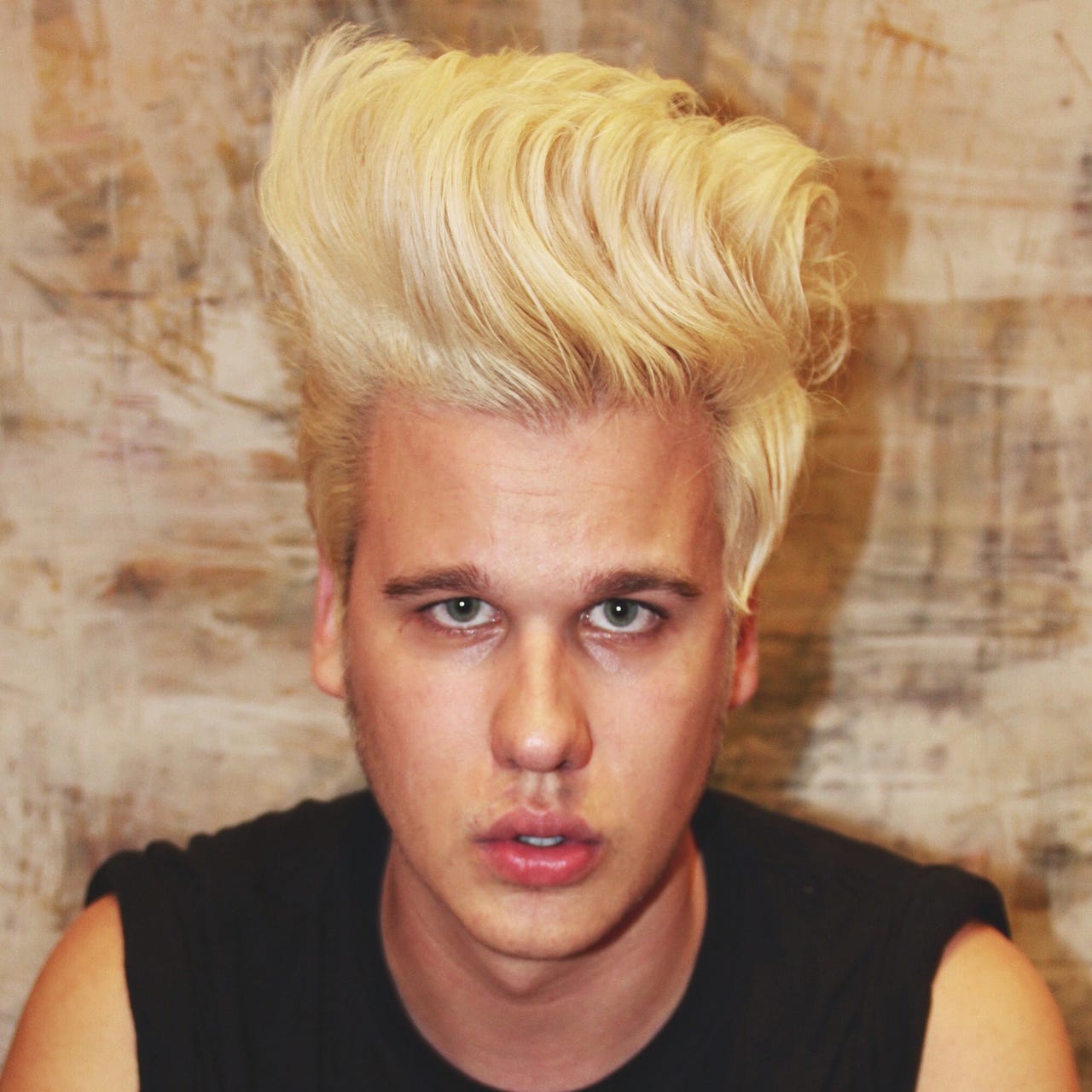

Cover art by: James Jeffers

Editorial assistant: Jesse Adele

You can follow my other unhinged missives by following me on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. My debut memoir, Born to Be Public, is out now.

Very relatable. Also, I'm a 16 on the scale but it's hard for me to count it up because aversion to certain numbers is part of my OCD and that always feels very ironic. Or maybe not. I can never remember what "ironic" is.

Milky gel pens... that’s detail work damn